“The Horror at Red Hook” is a short story by H.P. Lovecraft that first appeared in the January 1927 issue of Weird Tales. The protagonist of the story is Detective Malone, who investigates a series of kidnappings linked to a mysterious recluse named Suydam. The recluse has been involved in shadowy dealings with gangsters and other criminals operating in the slums of the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. The detective discovers that Suydam is the leader of a cult and the story climaxes with Malone witnessing a scene of human sacrifice and Lovecraftian carnage.

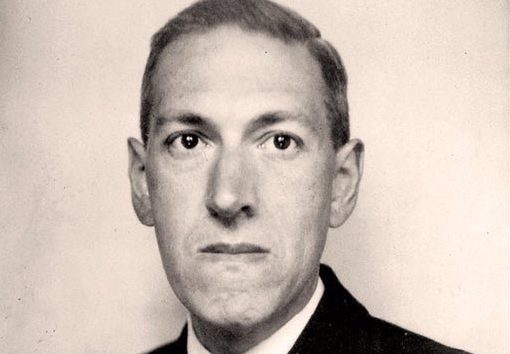

This is widely considered to be H.P. Lovecraft’s most notoriously racist story, and although you can easily find it online, it often gets left out of Lovecraft’s “Best Of” collections these days. Because the tale’s reputation preceded it, I opted out of reading it until I learned about Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom and decided I needed to read Lovecraft’s tale before I read LaValle’s novella.

I found Lovecraft’s story to be a frustrating but worthwhile read. I’ll discuss the problems I found in the story below, but I did find it useful partly because it gave me important insights into what LaValle is doing in his novella, but also because the final scenes of the story do contain excellent nightmarish imagery.

Having read “The Horror at Red Hook” for myself, I certainly agree that it’s Lovecraft’s most overtly racist story. The story’s central theme is that civilized, white America is under threat from the subhuman throngs of brown and black illegal immigrants seething in crowded ghettoes: “Policemen despair of order or reform, and seek rather to erect barriers protecting the outside world from the contagion.” Lovecraft describes a neighborhood of Asian immigrants as “slant-eyed folk” and later describes a sailor as “an Arab with a hatefully negroid mouth.”

Racism and xenophobia are front and center in this story. But having read several of Lovecraft’s other stories and novels, nothing in this story struck me as shocking or surprising. Racism and xenophobia are themes baked into Lovecraft’s work, but they’re usually camouflaged somewhat better than they are in this tale.

For instance, take his novella At The Mountains of Madness. The story is set in Antarctica, and all the characters are white men, so on the surface it doesn’t seem like there’s much opportunity for racism there. But the back story of the novella is that disaster struck the noble, alien Old Ones who’d colonized Antarctica when their slave-race, the shoggoths (dangerous black blobs of corruption, clever but lacking any ability to create or think at a high level) rose up and slaughtered them all. It doesn’t take a great deal of effort to realize it’s a metaphor for the white fear of freed African slaves destroying American civilization.

A big difference between the racism in At The Mountains of Madness and in “The Horror at Red Hook” is that Lovecraft doesn’t bother with metaphor in this story. But another critical difference between the two narratives, though, is that the racism and xenophobia in “The Horror at Red Hook” undermines Lovecraft’s world building, and that in turn damages the story.

I think about world building a great deal, particularly in cases where I’m creating a modified version of the real world. Whenever a writer sets out to create a work of fantasy, he or she has to work to “sell” the reader on the believability of fundamentally unbelievable elements. One critical way to ensure that a reader can properly suspend his or her disbelief for the duration of the narrative is to ground the story in as many real-world details as possible; the setting is a crucial place for this kind of grounding. So I was frustrated (but of course not surprised) that Lovecraft let bigotry get in the way of writing a well-thought-out piece of fiction.

The main thing that Lovecraft does to damage his world-building is to present us with melting-pot slums (“The population is a hopeless tangle and enigma; Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and Negro elements impinging upon one another”) with a recent illegal influx of Kurds, who have brought with them a Scary Oriental Cult:

Suydam, when questioned, said he thought the ritual was some remnant of Nestorian Christianity tinctured with the Shamanism of Thibet. Most of the people, he conjectured, were of Mongoloid stock, originating somewhere in or near Kurdistan – and Malone could not help recalling that Kurdistan is the land of the Yezidis, last survivors of the Persian devil-worshippers.

My head actually started hurting after I read that paragraph. It reminded me of some of the crazy pseudointellectual racist stuff my elderly male relatives spouted off about Those People (for whatever value of non-white ethnic group you care to insert there: I heard crazy, unfounded stories about them all). Further, the premise of the story’s plot is that Suydam recruits all these Spanish, Italian, Syrian, and black people as worshippers for his weird devil-worshipping Kurdish-Persian-Tibetan cult … because why? And how?

Because Those Brown People Are Evil. That’s all the story’s got. There’s no real explanation of why all these different ethnic groups would throw in with Suydam and join a new cult. The problem here is that real people cling tightly to their beliefs. Religious faith is powerful. If modern Satanists showed up in my hometown of San Angelo, TX and said “We bought out all the Thin Mints. We control the Thin Mints! Come worship with us!” I seriously doubt the local Baptists and Presbyterians and Catholics would reply, “Thin Mints, you say? Sold! Praise Baphomet!”

But that’s exactly the kind of scenario Lovecraft is putting forth here. He’s ignoring the whole vast history of religious conflicts happening after attempts at forced conversions and putting forth the unexamined, unsupported idea that all these different groups would be entirely fickle and easily subvertable in matters of faith.

So, I think this story is most useful to writers who want to study overt portrayals of racism (as an example of how not to describe people of color, for instance) and to examine the narrative malformations that this kind of unexamined bias can create. I’d have to stop short of recommending this story be read in a class, though, because I suspect a fair number of students would look at this and say “This is garbage and I’m not reading it,” and they wouldn’t be wrong.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.