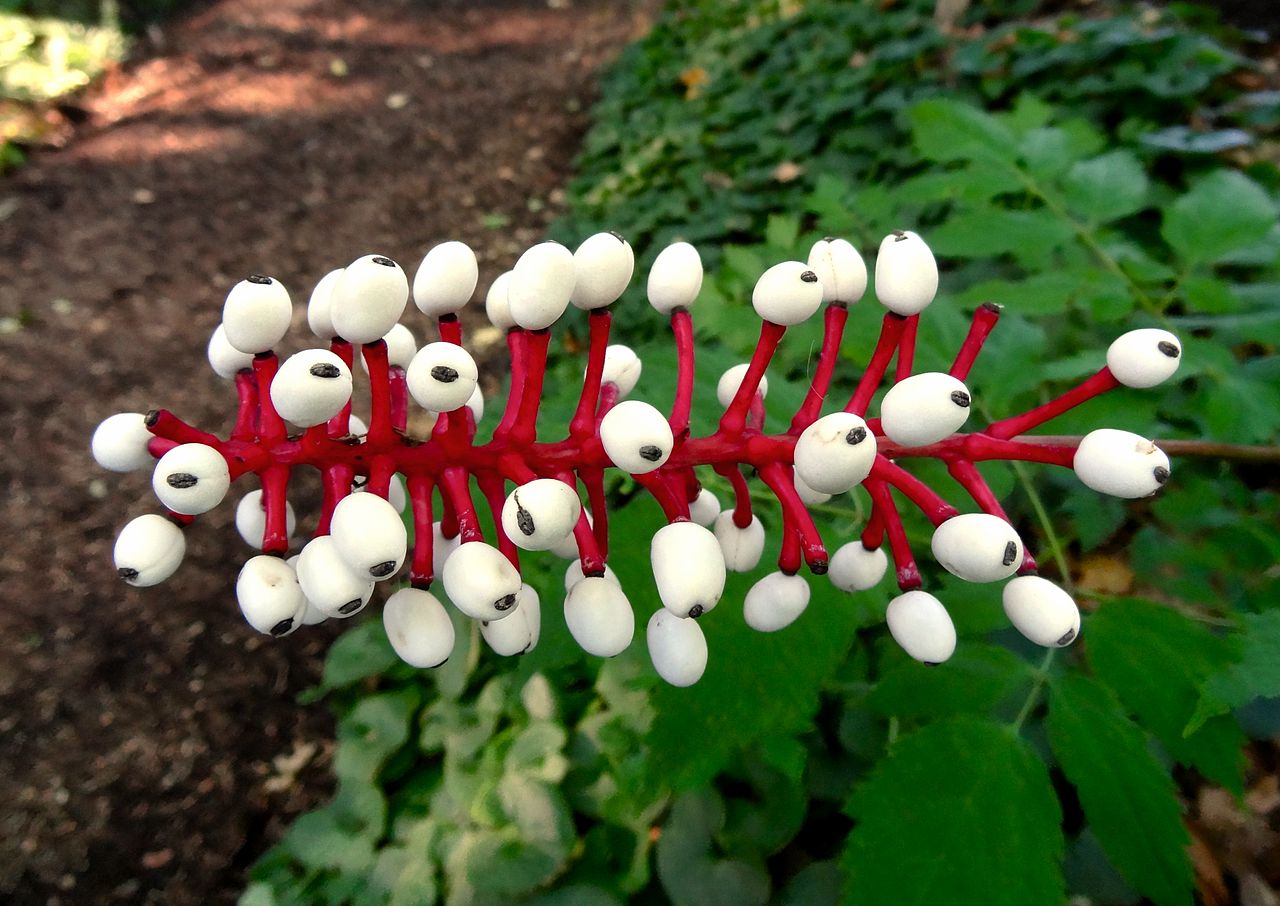

The classic Nathaniel Hawthorne tale “Rappaccini’s Daughter” tells the story of a young man named Giovanni who moves to Padua to be a university student. Every day from his rented room, he sees a beautiful young woman named Beatrice working in a strange and lovely garden full of poisonous plants. She is the daughter of a scientist named Rappaccini who has raised her to care for the dangerous plants he can’t touch himself; her exposure has made her immune but also turned her poisonous to others despite her apparent health and beauty. Giovanni falls in love with her, and of course things go awry from there.

Description was on my mind as I was reading this story, largely because I’d just taught my “Riveting Descriptions” workshop that morning and a few of my students’ questions were fresh in my memory.

One student remarked that she’d missed a great deal of the class-related metaphors and images embedded in the descriptions in The Great Gatsby the first time she read the book. She said, “I’m sure that people who read the book when it was first published would have totally gotten all those references, but me reading it 70 years later … I didn’t get it because it wasn’t my world. How do we write our stories so that people who read them years later will understand all the references?”

I told her, first, that thinking too hard about that is probably the road to madness. We can’t know if our work will be read even 5 years later, much less 70. It would be boring to go into a long, straightforward description of, say, Facebook now because everybody knows what that is. But 30 years from now? A teenager wouldn’t know. So we have to leave some clues, and anything important needs to be described or at least talked about.

I was thinking about that exchange when I encountered the description of the poisonous garden, which finishes with this line:

One plant had wreathed itself round a statue of Vertumnus, which was thus quite veiled and shrouded in a drapery of hanging foliage, so happily arranged that it might have served a sculptor for a study.

This description is clearly loaded with metaphoric freight. Vertumnus is the Roman god of the seasons and plant growth, and to have him shrouded here lends the line a sense of foreboding despite the artistic attractiveness of the arrangement. And it foreshadows Giovanni’s discovery that Beatrice is a spiritual sister to all the deadly plants in the garden and is poisonous herself. All that’s well and fine.

But as a modern reader, the problem I have with that line is that I don’t actually know what anything in that sentence looks like! What does the one plant look like, exactly? I have the vague sense that it might be a kind of ivy? But are the leaves pale or dark? Are there flowers? Maybe the plant doesn’t matter so much and we didn’t need that detail.

But then there’s Vertumnus, who does matter enough to be mentioned by name (otherwise, Hawthorne could have just written “a Roman god” and I’d picture some muscly white marble figure like Apollo and go on.) Vertumnus’ godly power is that he can change his shape at will. So what then does this statue look like? It seems there might have been some kind of popular image of the god in Hawthorne’s day, but seeing just his name doesn’t put any kind of accurately clear picture in my head any more than the image Hawthorne would conjure up if I’d gone back in time and whispered the phrase “Mini Cooper” to him. (He’d probably imagine a tiny man hammering together a wine barrel.)

One sentence from a story is a little thing. But my brain got hung up on it nonetheless, which may speak more to my state of mind than anything else. It does make me want to be more mindful when I have the impulse to use brand names as quick descriptive references — those brands won’t always be around, and I have to do more with them if those descriptions really matter.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.