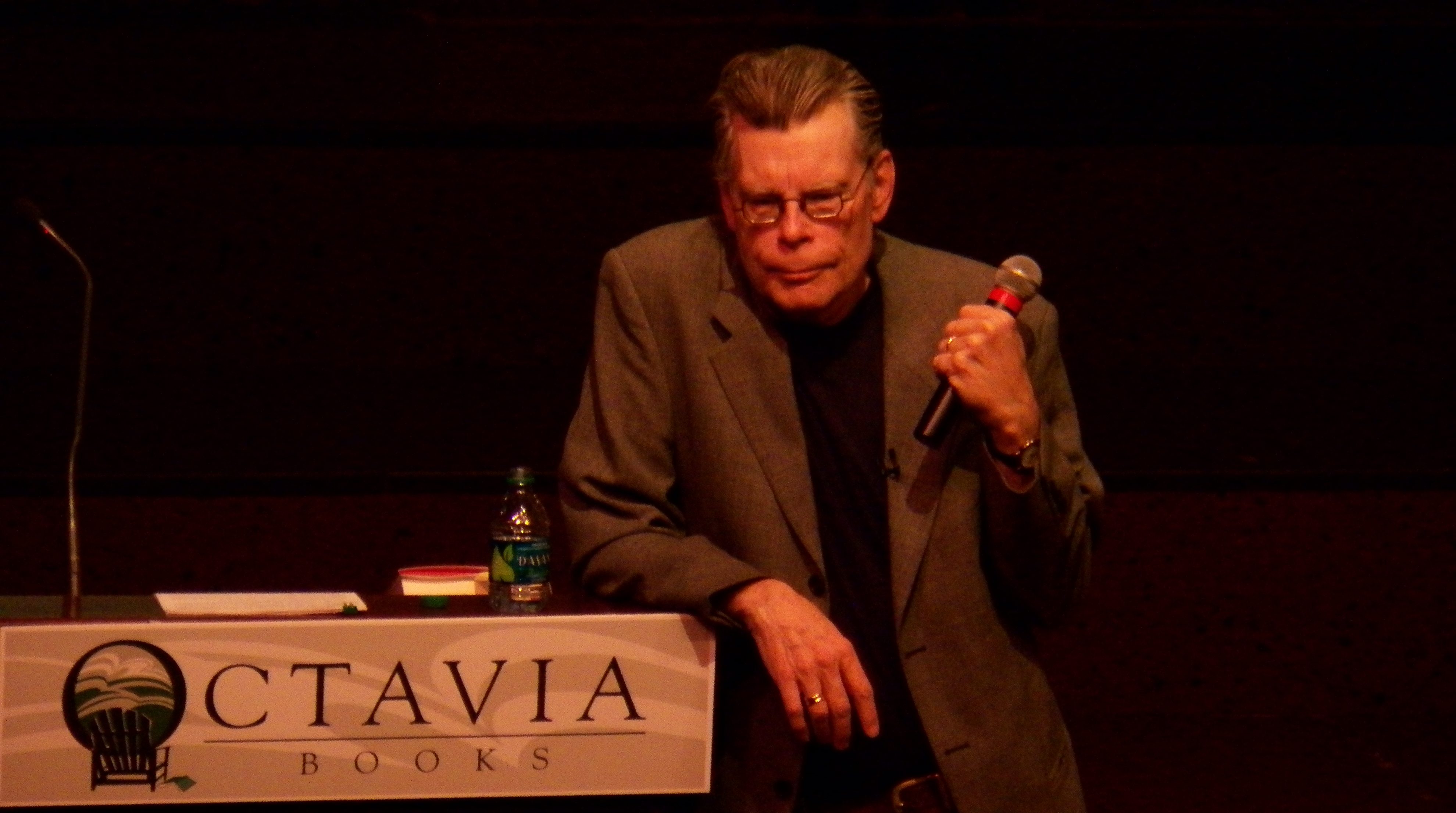

When I started reading Stephen King’s Dark Tower novels, one of the things that resonated with me is his introduction, “On Being Nineteen”, which is included in each book in the series (at least the editions I’ve been reading).

In his essay, King covers his motivations for starting The Gunslinger way back when he was just a teenager and details the book’s pop culture influences: Tolkien’s epic fantasy trilogy The Lord of the Rings and Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Western The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

(B)efore the film was even half over, I realized that what I wanted to write was a novel that contained Tolkien’s sense of quest and magic but set against Leone’s almost absurdly majestic Western backdrop.

This line particularly struck me because I realized I had a very similar kind of motivation for writing The Girl With The Star-Stained Soul. My goals for my novel are to take the kind of epic, chilling cosmic horror Lovecraft worked with and set it against my take on a classic Southern gothic setting. And, in doing so, tackle the racism in Lovecraft’s work (which was largely also my own white Southern ancestors’ racism) head on.

Which ties in with remarks King makes a bit earlier in his introduction:

I think novelists come in two types, and that includes the sort of fledgling novelist I was by 1970. Those who are bound for the more literary or “serious” side of the job examine every possible subject in light of this question: What would writing this sort of story mean to me? Those whose destiny (or ka, if you like) is to include the writing of popular novels are apt to ask a very different one: What would writing this sort of story mean to others? The “serious” novelist is looking for answers and keys to the self; the “popular” novelist is looking for an audience.

This is something I wrestle with. I don’t think that being a “serious” author and a popular one need to be mutually exclusive. But there’s a balance to be struck there, for sure. I know full well that many teenaged readers won’t give a toss about Lovecraft or his racism; I have to offer them a compelling, entertaining story. I have to be concerned with my audience and what my story will mean to them. Because, ultimately, if my book fails to find an audience, it won’t be read, and it will limit the opportunities for anything else I write.

But at the same time, I am still using the narrative to seek answers for myself; if I were solely interested in fiction writing as commerce, I could pick a topic far more marketable than this one. I am seeking those keys King mentioned. My novel’s function in this regard might be riding in the back seat, but it’s still there and part of the journey. This novel is in some aspects a dialog I can never have with long-dead relatives whom I have little in common with besides a few mysterious twists of DNA. Or perhaps it will simply function as a condemnation of and angry epitaph for a Southern culture that is receiving a well-deserved burial; I’ve never been especially good at speaking with my living relatives, much less the dead ones.

King wrote “On Being Nineteen” shortly before the National Book Foundation awarded him the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. And that award marked him as the kind of author he claimed to not be. May we all experience such irony in our writing careers!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.